It is the duty of the embalmer to create a memory picture… an illusion of pleasant, normal, restful sleep which will make the transition from life into death more majestic and easier for the family and friends to accept

(Strub and Frederick 1959, 11)

The belief that the dead must be restored to a life-like appearance to comfort mourners is a common folk psychology embedded in the modern American funeral industry. This concept is tied to the industry trope of the Memory Picture. The Memory Picture is the aesthetic styling, embalming, feature setting, and sensory staging of the dead for viewing. Its central claim is that aesthetic thanatopraxy (i.e. cosmetic embalming) will give the mourner a mental snapshot of their loved one appearing, not dead, but asleep. Looking upon their dead in this impersonation of sleep is presumed to provide grief support for the mourner (Laderman 2003, 22).

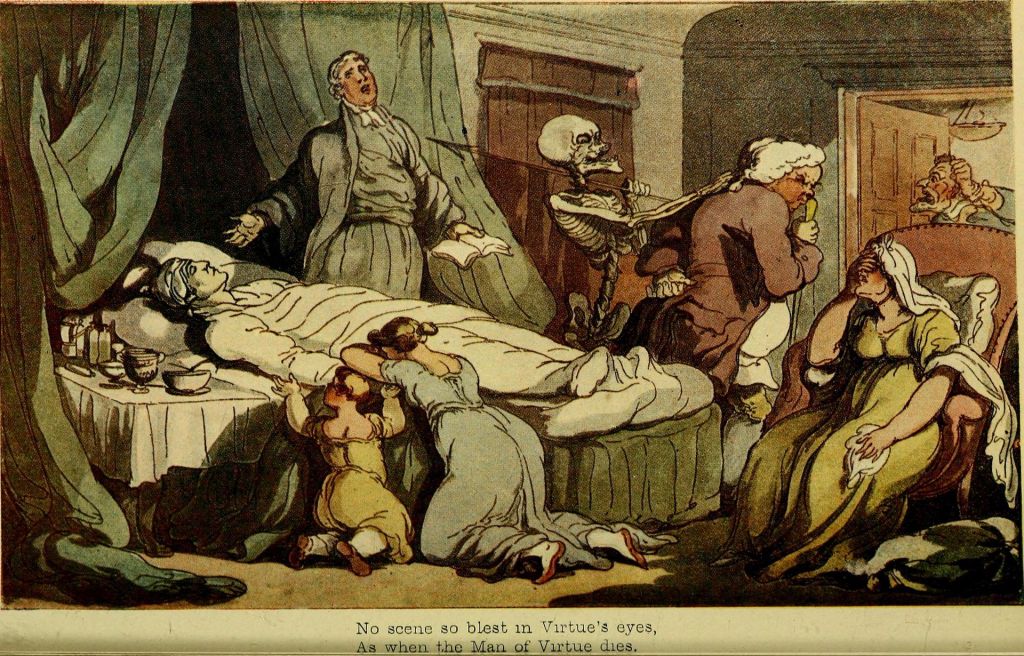

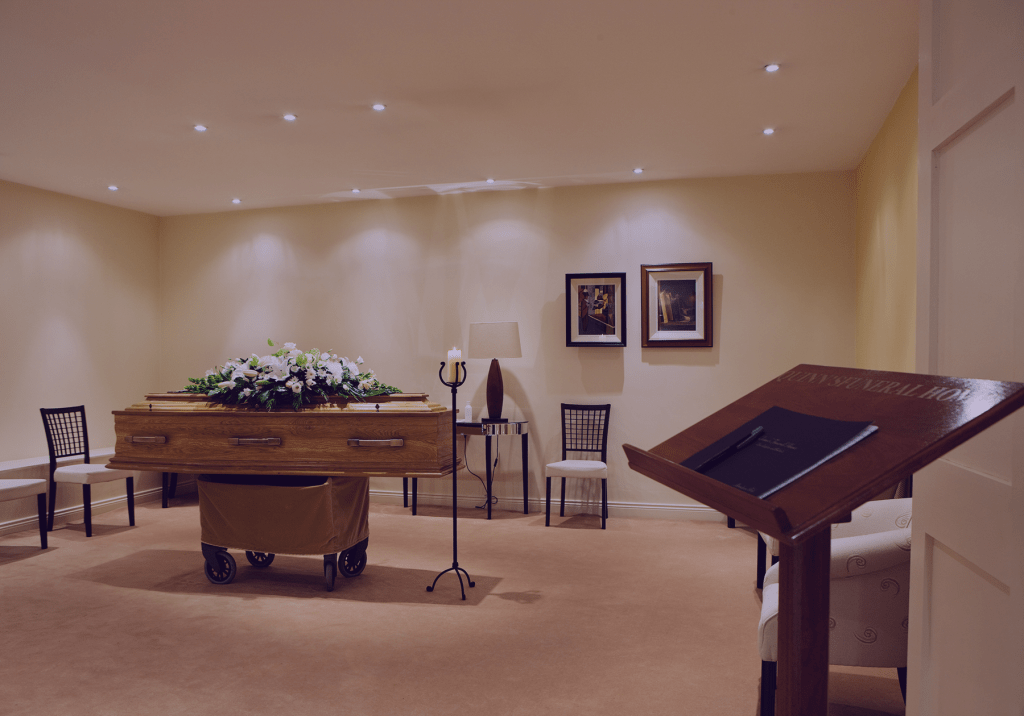

The staging of the Memory Picture is a meticulously orchestrated event that unfolds during an open casket viewing. It is a performance where the deceased assumes the role of the protagonist, supported by the funeral staff (Turner and Edgley 2009). The body is centre stage, dressed and laid in a bed-like casket, complete with pillows. Makeup and embalming techniques bestows a life-like appearance to the skin. Lighting and scent staging further enhance the scene, creating an illusion of peaceful slumber.

The viewing occurs in a dedicated room at the funeral home designed to accommodate the performance. These rooms give the impression of domestic or religious spaces, though they are neither. These business spaces utilise set dressing to appear like chapels and family homes.

Mourners, community members, and clergy do not participate in preparing the body for the performance of Memory Picture. Strict boundaries separate the mourners from the spaces within the funeral home, where one may experience the body without the dramaturgical act of the Memory Picture (Turner and Edgley 2009, 287).

As such, any comfort assumed from viewing the dead through this lens is not the result of the mourner’s embodied participation in the event. Instead, it is triggered by viewing as a passive spectator. The mere act of observing the tableau is presumed to incur the benefit. The funeral director’s aesthetic work-product claims to restore the naturalness of the deceased, yet they must protect the mourner from the natural reality of death. This protection is to prevent the assumed trauma of seeing a dead body.

However, to not view the body post-mortem is also presented by the funeral industry as perilous. Funeral marketing has told mourners for decades that unless they physically see their dead relative’s face, they may never truly accept the passing as real (Laderman 2003, 100). Therefore, the staging of the Memory Picture paradoxically protects the mourner from the psychological harm of viewing the dead and yet also provides the psychological closure only viewing the dead can afford.

These two contradictory states (seeing and unseeable) create the necessity for the performance of the Memory Picture, which only the modern funeral industry can provide. This highlights the significant influence and control that the modern funeral industry has over how we perceive and interact with death.

Yet, despite the herculean efforts to create the illusion of slumber in the performance of the Memory Picture, the mourner’s bodily schema is not easily misled. The sensory of death is not limited to sight. To achieve its goals, the Memory Picture must go beyond thanatopraxy and control the mourner’s senses and interactions with the dead through strictly curated access and performances.

Today, we will examine the history and evolution of the Memory Picture from both a dramaturgical and anthropological sensory perspective. All rituals are performances, but the Memory Picture has a unique artifice best analysed through sociological dramaturgy. Likewise, understanding the mourners’ embodied experiences, both before and after the normalisation of these tableaux, provides valuable insights into their effectiveness.

We will inspect the development of the Memory Picture through the changing norms of looking at the dead in the United States. While many aspects of funeral rites have remained consistent over time, care for the body and one’s physical proximity to the dead has profoundly changed. In the United States, the dead body has migrated from domestic space, where it was prepared by the mourners, to the public sphere, where they passively view it. This shift from active agent in private to passive viewer in public fundamentally changes what constitutes care and interactions with the body.

The Memory Picture is not a quasi-religious ceremony that inherently provides psychological comfort. Instead, the Memory Picture is a dramaturgical performance of customer service as a form of transactional care. Transactional care is the uniquely capitalistic inclination that the commercial transaction is the ritual. One can honour one’s dead through spending money on services for them—the more elaborate the production, the more care.

In pursuing high-level production, the Memory Picture was created not to aid in seeing the dead but to obscure them. It requires not only the staging of the body but also the filtering of visual reality through the public, photographic, and medical gazes. The public gaze is the societal norms and expectations that shape how the dead are perceived in social spaces. The photographic gaze is the artistic perspective which seeks to capture the deceased in an emotionally evocative composition. The medical gaze is the clinical detachment needed for the embalming process. Together, these gazes create the dramaturgical lens through which one views the dead within a funeral home.

One views, but one does not see.

These intersecting gazes structurally affect how we look and process reality within the funeral home. These lenses, by design, separate the mourner from the lived experiences of their dead, both positive and negative. The physical and sensory separation, along with the altered sight, is the protection promised by the Memory Picture.

Before the Memory Picture

To exist in the unfiltered sensorium with the dead is to acknowledge the state of death.

Space, Care, and the Body

The all-inclusive American funeral home is a product of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It would be unrecognizable to past American deathways. Nevertheless, its aesthetics continually appeal to tradition and history. Yet, the actors, objectives, rituals, and locations have transformed from communal and participatory to professional and passive (Cross and Warraich 2019). These appeals to tradition provide an aesthetic veneer of communal deathcare laid atop a modern for-profit business. Most importantly, the stylistic choices make the recent commodification of the dead body more palatable to consumers. Aesthetic calls to traditionalism give the impression that a professional has always conducted deathcare in a for-profit space.

In The American Way of Death, Jessica Mitford accurately assesses the error of traditionalism in the American funeral home, “A new mythology, essential to the twentieth-century American funeral rite has grown up— or rather has been built up step by step— to justify the peculiar customs surrounding the disposal of our dead… The first of these is the tenet that today’s funeral procedures are founded in American tradition….“ (1963, 17).

Mitford is, however, simplistic in her assessment of the past, “The most cursory look at American funerals of past times will establish the parallel. Simplicity to the point of starkness, the plain pine box, the laying out of the dead by friends and family who also bore the coffin to the grave.“ (1963, 16).

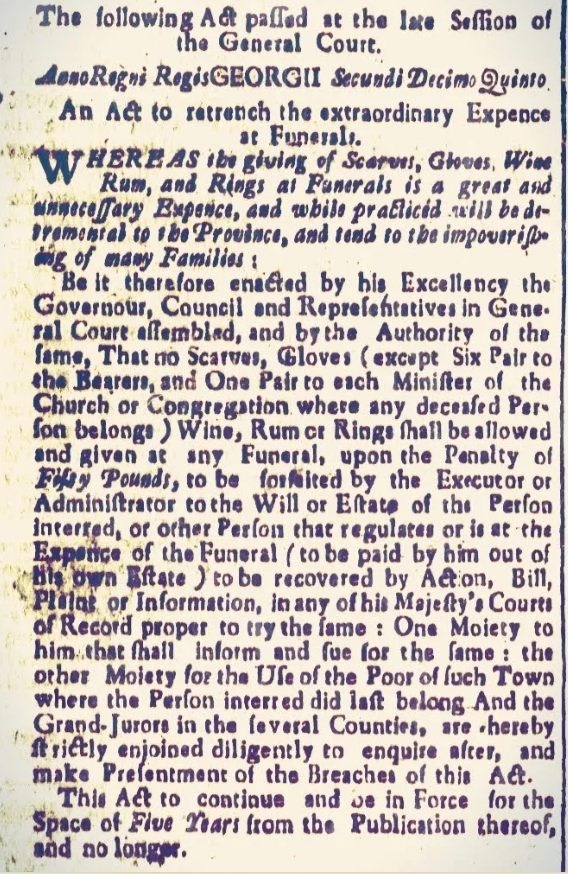

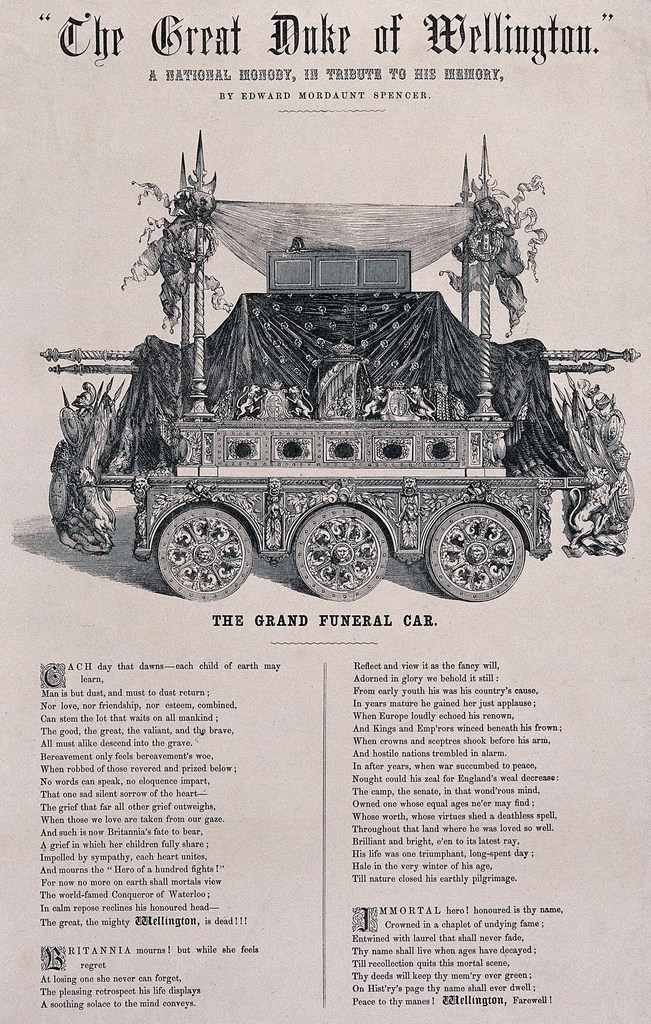

Early settler communities like the Puritans engaged in very austere death practices (Stannard 1977). However, there were transactional and socially performative elements of colonial and early American deathways. Dutch colonists to New Amsterdam introduced the first death professionals to the Americas, the aanspreker (death announcer) and huilebalk (professional mourner) (Jacobs 2004). There were also 18th-century practices of memorial gift-giving, mourning clothing, memorial paintings, and funeral feasts. Common memorial gifts included gold rings, scarves, gloves, clocks, and alcohol (S. Bullock 2012). This opulent spending became such an issue that sumptuary laws were put in place to control funeral expenditures (An Act to Retrench the Extraordinary Expenses at Funerals 1741). While Mitford’s plane pine box indeed did exist, so did the fine mahogany coffins by Anthony Hay and Benjamin Bucktrout of Williamsburg (Brennan 2007).

Public and Private Death

While Mitford oversimplifies the historical American funeral as it existed in the public sphere, she accurately identifies the consistency of the private-facing domestic elements, particularly around the care for the body. Care for the dead body was firmly in the domestic sphere for all of American society until the emergence of the funeral home. Women primarily did this work in their roles as family, friends, close community members, or domestic servants (Weaver 2016). This domestic care constituted the same acts women performed for living relatives. The objective of a vigil or wake was not the display of the dead but the guarding of the body before burial, prayers for the deceased, and comforting mourners.

The body did not require aesthetic styling in the domestic sphere because it was only to be viewed by one’s closest relatives. These were intimate acts in an intimate space. Other elements of the funeral may have been public performances, but the body was not a performer in them and was obscured inside shrouds and coffins. Even today, most funeral rites in the US require the face covered during the service.

Lamm and Eskreis assert that laying-in-state was historically reserved for sovereigns to confirm their deaths (1966). The intentional act of viewing an uncovered dead body was not practiced as a norm of historical American deathways before the mid-19th century (Lamm and Eskreis 1966, 138).

Caring and Sensing in the Domestic Sphere

Caring for the body and keeping it in the home before burial also put the experience of early grief within the sensory of the home. The mourner could look, touch, and kiss the dead without barriers. The acts of care towards the body, like washing and dressing, paralleled those done for family in life. Deathcare in domestic space gave opportunities to perform acts of love towards one’s dead.

Domestic deathcare was also a skill acquired through observation and training. These skills created the opportunity for sensory experiences with the dead and a personal understanding of decomposition. This was not always a pleasant experience. Coping with that reality was part of the skill of deathcare. The goal was to keep the body as whole and human as possible until it entered the grave. To exist in the unfiltered sensorium with the dead is to acknowledge the state of death.

Caring for the dead in the domestic sphere blended the sensory experiences of home, the interactions of grief, and the sensory of death. This state created a profound opportunity for memory-making and contemplation. The reality of death was simply an inevitable part of the human experience before the social rupture of modern embalming.

The Aesthetics of Death Through Public Eyes

These faces are depicted as sallow, with sunken eyes and gaunt cheeks to indicate the subject is dead, not sleeping.

The care and treatment of the dead changed dramatically in the 19th-century with the commercialisation of death practices in the United States. Acts once considered blasphemous, like cutting the dead, were reinterpreted as acts of care. This change was facilitated through the convergence of three states of perception (public, photographic, and medical), which form the dramaturgical lens of the funeral home.

While the medical gaze primarily affects the funeral practitioner, the public and photographic gazes are sculpted by the mourners’ interactions with the larger community. Historically, the nature of looking at the dead was ephemeral, emotionally intense, and intimate.

The body’s transition from the home to commercial death spaces placed the body and the family under social pressure to perform care to public aesthetic standards. Those expectations were influenced by lived experiences with the dead and the artistic depictions of death consumed by the public. The expectation for the dead to possess aesthetic beauty and visible signs of life has transitioned from art objects created in their honor to the body itself as an art-object.

Post-Mortem Paintings

19th-century post-mortem photography took inspiration from established memorial art traditions in the Americas, particularly paintings (Borgo and Licata 2016, 104). Early American posthumous paintings had two distinct styles; the European style used bright colors and depicted the subject before their deaths. The American style reinforced Protestant ideals of memento mori (Hollander 2017). The color palette in these paintings was muted, and the body shrouded in a bed or coffin. The coverings on the corpses were pulled back to reveal the subject’s face. These faces are depicted as sallow, with sunken eyes and gaunt cheeks to indicate the subject is dead, not sleeping.

Posthumous paintings show oscillating ideas on the visual depiction of the dead. In the 18th century, both the representations of life and death were acceptable. The dead body was not an unseeable trauma. Nevertheless, some preferred to present their dead as alive and active. These paintings reflect the changing perspectives on death, the afterlife, and the corpses’ place in public. However, this art was not intended to erase the sensory experience or memories of one’s dead.

Post-Mortem Photography

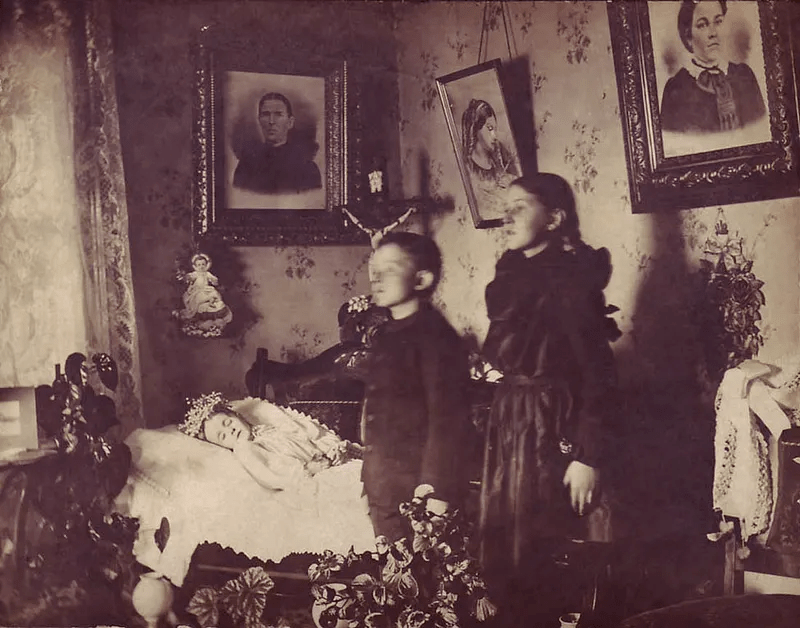

The aesthetic staging of bodies in the US began in the 1840s due to the popularity of photography. This was before the wide-scale introduction of commercial embalming or the funeral home. With the photo, there was no longer a separation between the memorial art object and the dead. The dead became part of creating the art-object. The photo became the frame and intersection (Lutz and Collins 1990) of the public and photographic gazes of the Memory Picture.

Before the American Civil War, the body was temporarily staged to be immortalized in the photo, not as an element of the funeral. These photos took place in the domestic sphere and were coordinated by the mourners. However, these images were intended for the public sphere and its rules of propriety. For instance, we rarely see adult women with their hair down or the dead in bedclothes. Nudity was reserved for marginalized bodies, such as executed criminals or anatomical cadavers. Considering the public gaze and the template of the memorial painting, certain realities of death became excluded from the visual depictions of the dead body.

The post-mortem photo presented a version of reality to be seen with a self-conscious awareness of social norms. However, there was no attempt to hide the early signs of decay in the flesh. Sunken eye sockets, discoloration, soft eyelids, drooping lips, and skin slip are common in 19th-century post-mortem photography. Little could mitigate the dead’s appearance at the time; interference with the body was socially discouraged, and depicting the dead as a corpse was already an established trope in memorial paintings.

The Photogenic Viewing

In the latter half of the 19th-century, the post-mortem photo turned from portraiture to tableaux, documenting the dead body and the living’s relationship with them (Borgo and Licata 2016). These post-mortem photographs show that by the late 19th-century, the liminal time before burial was no longer strictly confined to intimate domestic space. Also, consideration for artistic composition transferred from post-mortem portraits to tableaux and, eventually, the staging of the viewing itself. This socially conscious eye for funeral aesthetics was reinforced by etiquette manuals and sales catalogs, which presented ideas for styling and dress.

Coffins began to be propped at a 45-degree angle to display the dead better. The split-top coffin lid made it possible to view the face while obscuring the rest of the remains. Furniture, flowers, and potted plants would be arranged in the room with consideration to the artistic composition of the scene. Laying-outs moved from bedrooms and kitchens (intimate domestic space) to the parlor, the visually nicest room in the house intended for receiving the public. This consideration for public consumption led families to view these spaces and the dead within them as part of an artistic tableau. One’s taste and grief needed to be filtered through the photographic gaze to create the correct staging of the dead. However, this staging was focused on the visual presentation of the scene. The same aesthetic and olfactory concerns towards the body would not be adopted until the widespread acceptance of embalming and the application of the medical gaze to thanatopraxy.

Viewings and the Cult of Mourning

The American Cult of Mourning also significantly impacted the photogenic home viewing. Non-religious social events surrounding death became ritualised during the late 18th and 19th- centuries due to the consumption of cultural artifacts that memorialized death as an occasion greater than the natural cessation of life (Rizzo 2012, 148).

The American Mourning Cult was fostered by religious transitions in the United States, which changed the public perceptions of the afterlife. Fear of Puritan hellfire was replaced with a deeply sentimental memorialization and individuation through the public performance of mourning (LeeDecker 2007).

The photogenic lens gave the traditional wake the artistic consideration and framing to beautify, thus elevating itself into the type of aesthetic public mourning valued at the time. We see this transition in the language used for these at-home events.

Vigils and wakes hold religious significance. They focus on the protection and salvation of the dead. Laying-out was a term that initially encompassed the practical tasks between death and burial. All these words reflect the mourners’ actions towards the dead. They were praying, protecting, and preparing. Visitors were frequent at these events, but looking upon the dead’s unblemished face was not considered healing. In the late 19th-century, a new event, the viewing, came into use. This referred to a pre-funeral social gathering at the deceased’s home, where visitors would look at the body.

This subtle word transition underlies a profound alteration to the mourner’s expected action. During a laying-out, the mourner performed obligatory tasks for the dead without consideration for the aesthetic appeal of those tasks to bystanders. During a viewing, the mourner knew those tasks were presented for the public gaze. In the 18th-century, expensive memorial gifts reinforced social bonds and spoke to the family’s standing in the community. In the late 19th-century, the performance of the viewing did that function. The family had to embody and aesthetically perform cleanliness, social propriety, taste, morality, and the proper care for the dead. This performance was achieved through styling, influenced by artistic composition. The family orchestrated this staging to affect the memory-creation of the visitor, not themselves.

The public gaze created space between the visitor and the presentation of the family, both alive and dead. It did not yet exclude the familial mourner from the intimate sight of domestic death until the body fully transitioned to care in commercial spaces.

Professionalization and Seeing the Body

He looks as natural as though he was sleeping a brief and pleasant sleep

Embalming and the Medical Gaze

Before the Civil War, undertakers were part-time contractors who assisted the chief mourner with purchases. The funeral home developed as undertakers consolidated services and rented office space as funeral parlors. These parlors were fashionable and mimicked domestic space. This relieved some social pressure for hosting a viewing in one’s home. It also made the body the partial responsibility of the funeral worker, who was incentivized to extend the viewing as long as possible and maintain the body better than one could at home. It is with these customer service considerations that chemical embalming was introduced.

The US’s changing perception of chemical preservation (Trompette and Lemonnier 2009) of the dead was a crucial element in creating the Memory Picture, as the facsimile of sleep cannot be achieved without it. For most of American history, this type of preservation was associated with anatomisation. To pierce or perform violence towards the dead was desecration and a socially loathsome act. The body was to be revered as a person, not an object. In this worldview, anatomisation was a form of social annihilation, and it was used as corporal punishment by the state for that very reason (Humphrey 1973).

Modern American embalming originated directly in the anatomy lab. Before the rebranding to the antiquarian term embalming, the origins of embalming techniques were detested in the US. The rebranding began with the English translation of Jean-Nicolas Gannal’s Histoire des Embaumements in 1840, which became the seminal text for 19th-century American embalmers (Trompette and Lemonnier 2009).

The first embalmers in the United States were not domestic caregivers or undertakers but surgeons. These medical professionals were already familiar with body preservation from medical school. They would have been aware of Gannal and had access to the supplies needed for preservation. Most importantly, embalming requires practitioners to be comfortable with the medical gaze.

Foucault’s concept of the medical gaze describes the act of looking as part of diagnosing, in which the person is reduced to their injured parts (The Birth of the Clinic an Archaeology of Medical Perception 1973). Physicians were trained to objectify a patient’s body and compartmentalise their sight, filtering out non-biomedical material (Misselbrook 2013, 312). The medical gaze maintained a social and class distance between the physician and the patient. It also provided a psychological barrier between the physician and treatments that inflicted pain (O’Callaghan 2021). That distanced gaze allowed the surgeon-as-embalmer to violate the well-established taboo of bodily desecration in the name of aesthetics.

The Lincolns & Embalming as Care

Embalming was available in the United States through surgeons from the late 1840s, though it was rarely done. Abraham and Mary Lincoln’s acceptance and sentimentalisation of embalming were critical in normalising it to the American public.

Three deaths in particular changed the trajectory of corpse display in the United States. Firstly, the public lying-in-state of Elmer Ellsworth, the first Union casualty of the Civil War, introduced the concept of chemical preservation to the average American. At Ellsworth’s Washington funeral, Mrs Lincoln said, “He looks as natural as though he was sleeping a brief and pleasant sleep” (Groeling 2021, XV). This quote was reproduced in newspapers across the country. Prior to this, chemical preservation was something done to an anonymous and dehumanized corpse so that the body could be viewed in parts. Through the political drama of Ellsworth’s display, the public reinterpreted these same techniques as a means to maintain material and aesthetic wholeness.

The second pivotal case was the 1862 death of Lincoln’s son, William Wallace Lincoln. William’s death was not political theater, nor did his body have to endure an arduous journey. Instead, Willie Lincoln was embalmed as an act of care (Nylander 2019, 21). The popularity of embalming among Union soldiers would create the commercial embalming industry, but societal acceptance came from transforming acts once seen as desecration into a token of love.

Finally, in 1865, President Lincoln’s three-week traveling viewing brought embalming, post-mortem cosmetics, sensory staging, and artistic display together for a national demonstration of mourning. Yet, the president’s embalming was quite difficult, and he began showing signs of decay a few days into the procession (Fox 2015). Journalists reported on the condition of the president’s body and wrote opinion pieces about the ethics of prolonged viewing of the dead. However, the overarching perception of Lincoln’s viewing by the public was that it was a success that conferred great dignity on the tragic figure (Hodes 2015). Lincoln’s funeral became the aesthetic benchmark for the visual display of the dead. However, to achieve these new visual standards, the body must endure acts that would be understood as violence in the 19th-century, as the body still possessed personhood in death. The sight of these acts needed to be limited to those with the medical gaze for the final result to be acceptable as an act of care.

The Rise of the Memory Picture

In post-war America’s political and social landscape, death was considered an interruption of life.

Embalming services became widely available in funeral homes following the Civil War, and with it, caring for the body became professionalised. This new professional care involved hazardous chemicals and specialist equipment. The dead body was also reframed as a vector of disease that needed to be removed from domestic spaces and sanitised. The body would only be safe again after the “hygiene” of embalming. Regulation and professional accreditation limited who could perform these services and where. Professionalisation eliminated deathcare in the American domestic sphere. This deskilled the population regarding the care of their dead, making them reliant on paid services. It also removed the sensory experiences of death from the home.

Transfer of Audience

The sentimental public death of the late 19th-century continued in the US through the 1930s but was disrupted by World War II. The war caused an unprecedented scale of loss, which soured many Americans to the death customs of earlier generations (Armour and Williams 1981). The post-war period witnessed a steady shedding of the formalised public performances established by the 19th-century Cult of Mourning. This coincided with the growing importance of modernist and post-modernist discourse in the US, particularly regarding individualism. Death was one of many cultural narratives under scrutiny. The social pressure on families to perform proper funerals transitioned to a more individualistic approach to memorialisation (Valentine 2008).

Significant medical advancements across the 20th-century also led to people living longer and infant deaths declining by 90% (Meckel 1990). This profoundly changed the American experience of death. In post-war America’s political and social landscape, death was considered an interruption of life (Thomas 1975, 8-9). Death was thus the result of a technical failure to resuscitate the body (Cassell 1975, 43). This mindset normalized the hospitalisation of the dying and the administration of invasive medical procedures at the end of life (Chapple 2016). Death was to be fought until the bitter end.

With these social stressors, the Memory Picture took on its current form. The Memory Picture is not mentioned in funeral educational literature before the late 1950s. Prior to that, the funeral director provided these aesthetic services on behalf of the family so they could present the proper rituals for social esteem. Indeed, the criticism of funeral reformers of the time focused on selling tactics that exploited social pressures and obligations during an emotionally difficult period (Sher 1963).

Growing resentment over the state of commercial deathcare led to heavy criticism of the funeral industry in the 1960s. This was also during a period of budding corporatisation in the funeral industry. Corporatisation destroyed the veneer of community death that the funeral homes had cultivated for 60 years. As a result, corporatisation slowed, and the industry pivoted to provide the services their critics suggested as alternatives, such as direct cremation. This self-cannibalisation saved the funeral industry from mass disruption.

However, it did so at the expense of its premier product, staged viewings. Cremation is less expensive to produce and has few opportunities for add-ons. This may explain why the industry has never embraced cremation as its primary product. Viewings and formal funerals are still the prestige products the funeral home is designed to accommodate. To preserve the viewing as a viable service, the viewing needed to be recontextualised.

The New Viewing

The pressure of performance has moved from the family to perform for the dead and the community, to the staff to perform for the mourner as the paying customer.

From the 1960s onward, staged viewings became extravagant affairs with the intent of providing optimal service for the mourner as the premier customer. With relaxing social and religious norms, the viewing focused on personalisation and individualisation through consumerism (Valentine 2008). The ability to customise the experience is endless. Funeral directors became very aware of their poor reputations and adopted a warm, no-stress approach to sales, focusing instead on customer service to build a reputation that promoted the business.

With every material request accounted for, the remaining perceived needs to satisfy for the customer were emotional. In recent years, funeral directors have expanded into officiating services and increasingly positioned themselves as grief paraprofessionals. In Christian-centric funeral homes in the American south, the term ministry of care is an oft-repeated marketing phrase. This language frames the funeral director as a spiritual leader and the viewing as a healing ritual (Sanders 2009). These developments move the funeral director into a grey area of spiritual and psychological services.

The pressure of performance has moved from the family to perform for the dead and the community, to the staff to perform for the mourner as the paying customer. If death is a failure to revive, providing a life-like scene of the dead is an attempt to give the customer what they desire. As the funeral director cannot resurrect the corpse, they attempt to present a facsimile of life with the hope that it benefits the bereaved. However, by doing so, they also justify continuing their premier service in a new form, as a healing ritual.

The Dramaturgical Lens

Providing the facsimile of sleep, even in a symbolic capacity, requires shaping the viewer’s perceptions. Sensory information must be strategically deployed or concealed to present a restful tableau. The reality of death cannot be fully experienced. The Memory Picture is only possible by implementing the three structural gazes discussed earlier. The medical gaze is required to perform the tasks needed to create the Memory Picture. The photographic gaze is the self-aware aesthetic framing through which the Memory Picture is seen. The public gaze is the social consideration that determines what is and is not appropriate to be seen. The mourner can opt out of the photographic and public gazes through direct cremation or a closed casket, but to display the dead, they must abide by the social and aesthetic norms of viewing the corpse or risk ridicule.

Together, these gazes form the dramaturgical lens through which the Memory Picture is perceived in the United States. This lens pushes forward or filters out data about the dead body for the viewing as a performance. The viewing must be a highly choreographed experience for the mourner to be left with the impression of restful repose. The family can usually see the body un-embalmed in private if they request. However, many funeral homes will not perform an un-embalmed viewing as it defies the dramaturgical lens and refutes the value of the Memory Picture.

Theatre of the Dead

If the bereaved are to be given the impression that the loved one is really in a deep and tranquil sleep, they will have to be kept away from the area where the corpse is drained, stuffed, and painted for the final performance

Back of House

Violence must be inflicted on the body to create the aesthetics of sleep. To set the face, hooked eye caps are inserted under the eyelids, the jaw is sutured shut, and the lips are sealed with adhesive. In previous centuries, this would have been considered a symbolically significant desecration. However, by the early 20th-century, these tasks were accepted as a form of medicalised care. The body could be pierced to achieve aesthetic wholeness, just as a living body could be cut by a surgeon to be healed.

To achieve the Memory Picture, two viewers must be considered, the mourner and the embalmer, but their gazes contradict each other. The mourner wants to see the person’s humanity and he embalmer must see the body as an un-sensing object to perform their work. These contradictory states of perceiving are mitigated through the strict division of space in the funeral home between the front-of-house and the back-of-house.

The preparation rooms dominate the back-of-house in a funeral home. As with the theatre, the backstage regions are strategically hidden from the audience’s sight so the players can prepare for the performance without destroying the impression cultivated on stage (Turner and Edgley 2009, 287). As Goffman notes,

‘If the bereaved are to be given the impression that the loved one is really in a deep and tranquil sleep, they will have to be kept away from the area where the corpse is drained, stuffed, and painted for the final performance.“ (1959, 71)

In the back-of-house, the body is a medical object to the staff that can be seen naked or in decay (Turner and Edgley 2009, 290). There is no expectation of restful sleep. The embalmer is immune to the perceived dangers of viewing death through the distance of the medical gaze. The back-of-house also looks distinct from the front. Preparation rooms are stark and utilitarian. These are working spaces that resemble anatomy labs.

The back-of-house provides the visual cues that this is a business, and its primary product is the staging of the dead. This reality is counter to the presentations in the front-of-house. Therefore, the mourner cannot see the back-of-house. It will destroy the impression that the funeral home is a domestic space and force the mourner to see the actions needed to create the Memory Picture. Armed with complete knowledge of the process, they may choose to forgo the viewing, which would significantly impact the funeral industry.

Front of House

The front-of-house is a carefully curated execution of architecture and interior design to give the impression of a comfortable communal gathering spot (Harper 2010, 108). The funeral home wishes to present itself as a home away from home and mimic domestic space. As such, many of the rooms customers visit give the impression of a bed and breakfast. It is not quite a home, but neither does it feel commercial.

The color pallet is kept neutral, and the furniture are American living room staples. Some funeral homes have full kitchens to facilitate a repast on-site, adding to the space’s domestic feel. Offices tend to be in the back; preferably, customers would spend little time there. Livingroom-like arrangement rooms are where most funeral home business is conducted. The display room, which holds samples of available merchandise, is the only room that betrays the front-of-house as a commercial space.

The Stage

Dedicated viewing rooms or funeral chapels within the funeral home regularly take on the appearance of religious spaces. Chairs are arra nged like pews with a central aisle (Harper 2010). The casket is the main focal point, with furniture, flowers, draping, and photos decorating the area like an altar. A lectern stands off to the side like a pulpit to facilitate speakers. Viewing rooms frequently have multiple entrances to facilitate the staff quickly and unobtrusively moving through the space like stage wings (Turner and Edgley 2009).

The viewing room is designed to sculpt the visitor’s sensory experience of the body. These rooms are rarely naturally lit but tend to have soft and low interior lighting. Many funeral homes use pink-tinted bulbs to further cancel out skin discoloration on the corpse. The viewing will be scored with live or recorded music. The family and funeral director carefully select the musical choices to present the appropriate emotionality to the scene. As in theatre, music serves as a cue for events and emotional tempo changes.

Temperature and odors are also controlled in the room. Ambient odors are used for emotional priming. Stamens will be cut from lilies to not overwhelm the audience with a strong indolic aroma, as white florals can remind people of decay. Baking cookies or boiling onions offstage are well-known techniques to create the comforting scent of home. High-tech odor systems like Airscent specifically market to the funeral industry to create seamless pre-planned olfactory staging for viewings.

The Performing Corpse

The corpse was once the inspiration for the memorial painting, then a participant in creating the post-mortem photo, and now the corpse is the art-object itself. The body is re-personalized through the artistic transformation of embalming and display (Harper 2010, 108). The aesthetic thanatopraxy of embalming, feature setting, and mortuary cosmetics are to give the dead a life-like appearance for the mourner’s benefit. As such, the mourner’s senses are the primary consideration.

Powerful odor neutralizers like Neutrolene are used internally and externally to eliminate foul smells from the corpse. Scented arterial and cavity fillers are available, including solutions specifically designed for infants that are fragranced with baby powder. The preservative nature of formalin-based fillers slows the odor of decay but has a harsh chemical smell that can radiate from the body in certain circumstances. These scented products mask those chemical odors and re-establish an appropriate scent of personhood.

The embalmer will carefully consider the formaldehyde index of their products. Formaldehyde stiffens flesh, but too much makes the skin feel hard. Attention is paid to the hands and face as these are the areas most likely to be touched by mourners. Emollients can be co-injected or applied to the skin to give these areas a more life-like feel. However, touching beyond a gentle pat is discouraged both socially and by the nature of the body’s position in the casket. The temperature of the skin is also considered. Dead skin will be colder than living, but presenting the body at room temperature will make it feel closer to normal.

The primary sense considered in preparations, however, is sight. Dyes are added to embalming fluid to recreate the undertone of living blood. Skin stains are bleached to produce an even skin tone. The body will be fully dressed, including undergarments, to give the proper structure. Makeup is applied to mimic living skin and facial contours. Skilled technicians use restorative wax to recreate missing facial features or add volume. Realistic facial reconstruction is difficult to obtain as it requires mastery of sculpting life-like facial features and melding them to existing anatomy. Failure to flawlessly execute a reconstruction will make the face appear mask-like, thus breaking the illusion.

The body is the lead player in the performance, and it has the burden of beauty labor through the proxy of the mortician. The aesthetics of the body is the mortician’s work-product. Before the aesthetic styling of the dead was normalized through staging and the Memory Picture, this beauty labor was not expected. If the body cannot maintain this illusion or the funeral director does not have the skill to execute it, the Memory Picture fails and can create feelings of un-realness or uncanniness. This un-ease is a failure of the funeral director to achieve the promised work-product. To avoid that, successful funeral directors are skilled at assessing the body and their ability to create a Memory Picture. If the performance cannot execute a sufficient denial of death, it is not good customer service to do it.

The Supporting Cast

The collapse of home deathcare, the secularization of funeral rites, and the commercialization of death have turned the funeral director into the gatekeeper for a profound lifecycle event, one’s confrontation with the deceased. The funeral director justifies their intervention through the thanatopraxy of the Memory Picture as necessary, even noble (Trompette and Lemonnier 2009, 24). Through their skilled hands, they attempt to transform this event from an anxious confrontation with reality to a gentle recollection of a preferred existence. The funeral staff does not see themselves as performers but as stand-ins for religious caretakers (Chamboredon 1976, 665-676) who produce symbolic goods like comfort (Bourdieu and Nice 1980, 261).

Staff at the viewing serve as the supporting cast to the body’s performance. They monitor the stagecraft to determine the success of the presentation. Sensory inputs will be modified to maintain the illusion for the audience. The culminating moment of the funeral staff’s performance is when the deceased’s family approaches the body to experience the Memory Picture. This moment will determine if they succeeded in providing quality service.

The Mourner

The chief mourners are the audience for the modern Memory Picture (Turner and Edgley 2009). It is their experience of the aesthetic work-product that is valued over all other attendees of the viewing. The funeral staff has primed them to see their loved one in a state of peace and rest. Those abstract concepts are interpreted through the impression of sleep in the body. The mourners are told the dead will look natural, which is to say alive, as the aesthetics of death are unnatural through the dramaturgical lens. In the pursuit of naturalness, the body is in a supreme state of unnaturalness. The mourner is told the staff’s thanatopraxy will return the dead to dignity. This means that not only death but signs of illness or injury will be obscured from the mourner’s view. The implication is that universal experiences like death, illness, and injury are humiliations that need to be obfuscated for the dead to maintain social esteem in this setting.

The chief mourners are usually the first ones to enter the viewing. If the staging is done correctly, the sensory guides will be unperceivable as an artifice. The mourners will not notice the pink lights, ambient odors, or the working areas of the facility. They will just see the posed body. Their role in the Memory Picture is to observe through the dramaturgical lens. They are not active agents creating this scene beyond their purchasing choices. Nor are they encouraged to interact too much with the body.

By looking at the remains in this state, the mourners are primed to feel a sense of accomplishment in selecting these services. They have done right by their dead. They are also to feel relief from anxiety or fear. The meeting with death has been tempered. The realities of the human experience are augmented so the mourner does not have to confront them. This is presented as a positive. The Memory Picture saves the mourner from grief and gives them a beautiful memory for their final encounter.

This staged memory is to be so powerful that it expunges earlier memories of illness and dying. The mourners are willing participants in this performance and want it to succeed, but the performance does not always go as planned. No one is genuinely convinced that the dead are asleep. However, for the Memory Picture to be successful, the performance must be convincing enough to avoid the reckoning with death. Even still, people often expeirence and uneasiness at viewings created from the un-canny valley between the performance and reality.

Conclusion: Mourning Through Glass

one must look upon the dead with compassion and courage

The Memory Picture’s grief support claims are based on the avoidance of existential death anxiety through sensory distancing between the viewer and the confrontation with mortality. Yet, academic consensus shows that caring for one’s dead and being in their unaltered presence allows for catharsis. It does so because it is a fully embodied experience, both profound and terrible, that enables the living to come to terms with death on an individual and existential level. Limiting participation to sight helps the Memory Picture achieve its aesthetic objectives of avoidance but may not serve the complete sensory needs of the mourner.

Instead, the Memory Picture is recasting a commercial practice as a beneficial ritual. This recasting was done to give an older thanatopraxy renewed relevance. No substantive changes occurred to the techniques, only how they are marketed to families. The funeral industry wants its customers to feel positive about their work. In giving the mourners what they think they want, the funeral director may strip them of their needs.

The Memory Picture does not allow for viewing the dead; it obscures them. To truly have that sight, the dramaturgical lens must be removed, and one must look upon the dead with compassion and courage.

Bibliography

- 2023. 2023 Annual Statistics Report. Industry Report, Wheeling: Cremation Association of North America. https://www.cremationassociation.org/page/IndustryStatistics.

- An Act to Retrench the Extraordinary Expenses at Funerals. 1741. Chapter 14, Section 1, p. 1086 (Provance Law, Boston).

- Armour, R., and C. Williams. 1981. “Image making and advertising in the funeral industry.” Journal of Popular Culture 14 (4): 701.

- Borgo, M., and M., Iorio, S. Licata. 2016. “Post-mortem photography: the edge where life meets death?” Human and Social Studies 5 (2): 103-115.

- Bourdieu, P., and R Nice. 1980. “The production of belief: contribution to an economy of symbolic goods.” Media Culture Society 261-293.

- Brennan, K. 2007. The Bucktrout Funeral Home, a Study of Professionalization and Community Service. Thesis 1539626538, Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. William and Mary Univeristy. doi:https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-26m3-cx36 .

- Brenner, E. 2014. “Human body preservation-old and new techniques.” Journal of Anatomy 224 (3): 316–344.

- Bullock, S, and S McIntyre. 2012. “The Handsome Tokens of a Funeral: Glove-Giving and the Large Funeral in Eithteenth-Century New England.” The William and Mary Quarterly 69 (2): 305–346.

- Cassell, E.J. 1975. “Dying in a Technological Society.” In Death, Inside Out, edited by P. Stienfels and RM. Veatch. New York: Harper and Row.

- Chamboredon, J.C, 1976. “Sociologie et histoire sociale de la mort: transformations du mode de traitement de la mort ou crise de civilisation?” Revue Francaise de Sociologie 17: 665-676.

- Chapple, A; Ziebland, S. 2010. Viewing the body after bereavement due to a traumatic death: Qualitative study in the UK. British Medical Journal, 340, c2032. doi http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2032.

- Chapple, H. 2016. No place for dying: Hospitals and the ideology of rescue. Routledge.

- Cross, SH., and HJ, Warraich. 2019. “Changes in the Place of Death in the United States.” New England Journal of Medicine 24: 2369-2370. doi:doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1911892. PMID: 31826345.

- Foucault, M. 1973. The Birth of the Clinic: an Archaeology of Medical Perception. Translated by AM. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Fox, RW. 2015. Lincoln’s body: a cultural history. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City: Doubleday.

- Gray, M. 2020. “Deathbeds and Burial Rituals in Late Medieval Catholic Europe.” In A Companion to Death, Burial, and Remembrance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe c. 1300-1700, 106–131. Boston: Brill.

- Groeling, M. 2021. First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, The North’s First Civil War Hero. El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie.

- Haas. R. 2003. Bereavement care: Seeing the body. Art & Science Nursing Standard, 17(28).

- Harper, S. 2010. “Behind Closed Doors? Corpses and Mourners in English and American Funeral Premises.” In The Matter of Death: Space, Place, and Materiality, edited by J. Hockey, C. Komaromy and K. Woodthrorpe, 100–116. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hodes, M. 2015. Mourning Lincoln. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hodgkinson, P. 1995. Viewing the bodies following disasters: Does it help? Bereavement Care, 14 (1), 2-4. doi: 10.1080/02682629508657346

- Hollander, S. Exhibition Curator. 2017. “Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America.” New York: The American Folk Art Museum.

- Humphrey, D. 1973. “Dissection and discrimination: the social origins of cadavers in America, 1760-1915.” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 49 (9): 819.

- Jacobs, J. 2004. New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeen-Century America. Brill.

- Laderman, G. 2003. Rest in peace: A cultural history of death and the funeral home in twentieth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lamm, M., and N. Eskreis. 1966. “Viewing the Remains: A New American Custom.” Journal of Religion and Health 5 (2): 137-143. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27504786.

- LeeDecker, C. 2007. “Preparing for an afterlife on earth: The transformation of mortuary behavior in nineteenth-century North America.” International handbook of historical archaeology 141-157.

- Lutz, C., and J. Collins. 1990. “The Photograph as an Intersection of Gazes: The Example of National Geographic.” Visual Anthropology Review 7 (1): 134-149.

- Meckel, RA. 1990. Save the Babies: American public health reform and the prevention of infant mortality, 1850-1929. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Misselbrook, D. 2013. “Foucault.” British Journal of General Practice 63 (611): 312. doi:doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X668249.

- Mitford, J. 1963. The American Way of Death. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Nylander, S. 2019. “Death, American Style: Americana and a Cultural History of Death.” In Death in Supernatural: Critical Essays, 16–34. McFarland.

- O’Callaghan, A. 2021. “The medical gaze”: Foucault, anthropology and contemporary psychiatry in Ireland.” Irish Journal of Medical Science 191 (4): 1795-1797. doi:doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02725-w.

- Rizzo, TM. 2012. “The Cult of Mourning.” In Edgar Allan Poe in Context, edited by KJ. Hayes, 148–156. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sanders, G. 2009. “The Contribution of Implosion to the Exuverance of Death.” Fast Capitalsim 5 (1). https://fastcapitalism.uta.edu/5_2/Sanders5_2.html#_edn4.

- Sappol, M. 2004. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton University Press.

- Sher, B. 1963. “Funeral Prearrangement: Mitigation the Undertaker’s Bargaining Advantage.” Stanford Law Review 15 (3): 415–479. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1227305.

- Stannard, D. 1977. The Puritan way of death: a study in religion, culture, and social change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Strub, C, and L Frederick. 1959. The Principles and Practice of Embalming. Oakland: The University of California.

- Thomas, L. 1975. Anthropologie de la Mort. Paris: Payot.

- Trompette, P., and M. Lemonnier. 2009. “Funeral embalming: the singular evolution of a medical innovation.” Science Studies 22 (2): 24.

- Turner, R., and C. Edgley. 2009. “Death as Theater: A Dramaturgical Analysis of the American Funeral.” In Life as Theater: A Dramaturgical Sourcebook, edited by D. Brissett and C. Edgley, 285–298. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Valentine, C. 2008. Bereavement Narratives: Continuing Bonds in the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge.

- Weaver, K. 2016. “Painful Leisure and Awful Business: Female Death Workers in Pennsylvania.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 140 (1): 31–55. Accessed Feb 26, 2024. doi https://doi.org/10.5215/pennmaghistbio.140.1.0031.

- White, C., Fessler, D. 2013. Evolutionizing grief: Viewing photographs of the deceased predicts the misattribution of ambiguous stimuli by the bereaved. Evolutionary Psychology, 11(5). 1084-1100.

You must be logged in to post a comment.