With the success of movies like Coco and The Book of Life, along with the popularity of children’s books like The Dead Family Diaz, it is clear that the English speaking world is more familiar than ever with Día de Muertos (aka Day of the Dead). Overall I think this is a good thing. Latin American civilisation, in general, and Mexican cultures, in particular, have a lot to teach the Anglo world about culturally confronting death. Then again, the necessity to create that confrontation was born out of struggles that are rarely discussed in the coverage of Day of the Dead festivities. While sugar skulls and La Catrina makeup have become fashionable Halloween options, a deeper understanding of the history and rituals of Día de Muertos is still eluding a lot of the appreciation of the holiday by outsiders. Today we are going to go in-depth about one aspect of this rich cultural tradition, that being the use of copal and the part olfaction plays in Día de Muertos rituals.

Before We Begin

So before we get into the smoke, let’s start by dispelling a few misconceptions about Día de Muertos, it is not ‘spicy Halloween’ as one very obtuse friend shared with me a few years ago. The similarities between Halloween and the Day of the Dead arise from both the indigenous cultures of Ireland and Mexico being profoundly agrarian and bound to agricultural calendars. Their indigenous religions reflected the cosmology of those calendars. Both cultures confronted Christian colonisation and adapted, assimilated, and/or synchronised to survive. That is where the similarities end.

Christianity came to Ireland around 400 CE, Spain showed up in modern-day Mexico in the 16th century. Samhain, (the pre-Christian Celtic harvest festival) lost religious significance and its customs synchronised with All Hallows before becoming secularised and commercialised in the US as Halloween; where it is enjoyed by people without cultural or religious connections to Samhain. Meanwhile, Día de Muertos still pulls from the pre-Colombian tradition of Hanal Pixán and the Aztec festival to Mictēcacihuātl, the Goddess of Death, in ways both intentional and unintentional. These celebrations synchronised with Christianity, but are also deeply rooted in one’s own experience of death, loss, position in society, and one’s sense of ethnic/national identity.

Not every region of Mexico celebrates Día de Muertos or in the same way. The Maya of the Yucatan celebrate Hanal Pixán by cooking mucbipollo. Tarascan fishermen light torches and sail out in their elegant butterfly-netted boats to the cemetery on Janitzio island in the centre of Lake Pátzcuaro. They look like beautiful ghost moths floating on a sheet of obsidian. At the same time, wealthy urbanites of Mexico City can be seen gawking at the celebrations in Mixquic, as much removed from the intensity of the scene as the tourists from Cincinnati they are standing next to.

Also, versions of Día de Muertos exist throughout Latin America, and there are about 40 memorial festivals that bear a similarity to Día de Muertos. We will be focusing mostly on Mexico’s practices in Mexico City, Oaxaca, Chiapas, the Yucatan and to a lesser extent the highlands of Guatemala.

Incense Americano

So let’s begin at the beginning, what is copal?

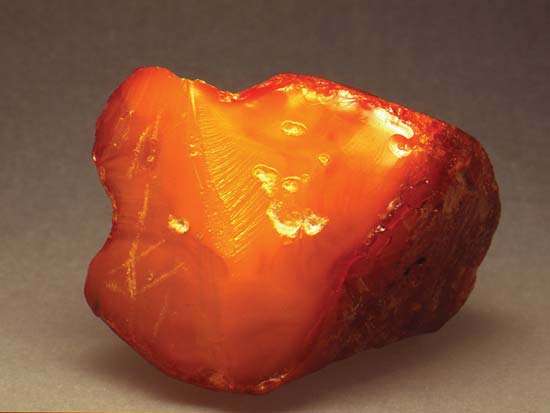

Copal has become a bit of a misnomer for resins from all over the world, but in modern times, we are speaking of the product of the Bursera Bipinnata tree. In the past, it wasn’t so easy to identify the best copal producing trees so the material was harvested from a variety of sappy sub-species which can make identifying ancient fossils as copal a bit of a pain, but if you go to the market these days you are getting material from the Bursera.

These trees are endemic to Mexico and Central America where they can be found in the lush shade of tropical forests. They produce a heavy milk-like sap that dries naturally into a beautiful gummy resin and given enough time can fossilise into amber. Copal resin can be harvested with no more technology than a pocket knife, some duct tape, and a Coke bottle, making it an accessible source of income for poor rural people. These trees are also bountiful, fast growing, and recover quickly from the collection process. All of this makes them ideal for long-term aromatic production.

Though copal is a staple in the aromatic landscape of the Americas, it is rarely exported to the States. Copal resin isn’t a significant fragrance component, and most incense users in North America are more familiar with charcoal-based fragrance-infused cones than with the burning of raw aromatic materials over direct heat. This is probably a good thing. While the world’s hunger for materials like oud is putting those trees at risk of extinction, copal is doing ok*.

Copal ranges in colour and quality depending on which tree was sourced, its age, and any inclusions in the sap. Excellent quality resins can be found in most markets in Latin America for a reasonable price. It is not uncommon to see it by the kilo. To me, the scent is much softer than other tree resins and maintains a pleasantly clean, but slightly oily, woodiness; with a floral almost lemon aspect. It reminds me of fresh cut blonde wood. Though it burns at almost twice the rate of other incense materials like myrrh and frankincense and has a tendency to smoke, it is worth it for the heavenly aroma.

Copal resin has often been called the frankincense of the Americas for being the premier aromatic resin of the region and its similar importance in trade and religion. Copal’s use has traditionally been as an incense and in fact, gets its name from the Nahuatl word, copalli, for burned aromatics. This gummy resin also has a history in traditional medicine, as a glue (famous for setting jade inlays into Aztec courtier’s teeth) and a varnish, but by far its most important function is and has been, religious.

Food of the Gods: Corn, Blood, and Copal

Before we can discuss the importance of copal to the Day of the Dead we have to understand the critical role copal played in pre-Colombian Mesoamerica. Its value to both Aztec and Mayan cultures is evident by the effort to produce, store, and trade the product, but copal wasn’t for scenting one’s home for a chill atmosphere. It was the food of the gods.

I mean that quite literally. Copal was seen as a necessary sacrifice that must be offered daily to sustain and nourish the deities. There was a parallel in the minds of ancient Mesoamericans between maize and copal. Maize was the food of humans, but copal was the food of deities, and just as essential to the continuation of daily life.

Excavations in and around Lake Chapala and Nevado de Toluca show that copal’s gummy resin was moulded into ceremonial corn cobs up until the Conquest. They were even wrapped like tamales and given as offerings alongside actual maize offerings. The lake offerings (probably for the rain/fertility/water god Tlaloc) were thrown into the water unburnt, while incense braziers discovered near the lakes would have been used to consume vast quantities of copal. Many Aztec braziers include maize in their adornments as well as depictions of Chicomecoatl, the Goddess of Nourishment, holding maize in her hands.

Small balls of copal found in the ceremonial well at Chichén Itzá were painted greenish blue, and some were embedded with pieces of jade. The Maya had a custom of placing small lumps of jade in a corpse’s mouth to symbolise maize. This jade-maize served as spiritual food for the soul to use in the afterlife. Like an amuse bouche for the underworld. The jade-painted copal offerings found in the well may have served as a memorial offering, a spiritual snack if you will.

The braziers and the water offerings show two different ways ancient people’s used valuable aromatic materials to interact with divinity. One was a form of nourishment and shared communion. The sacrifice of an expensive article made in the hopes that the god would be equally pleased and share food with the people in the form of rain and healthy crops. But there is also a kind of sympathetic magic there as well. Just as they burned food for the god, sending sustenance and prayers through ethereal fragrance, they also were creating big black plums of smoke like the black rain clouds they wanted to manifest in the world.

While the connection between copal and maize was consistent throughout almost 2,000 years of Mesoamerican history, there was a variety of beliefs and beliefs changed over time. The Lacandón, a Mayan people who live in the modern-day state of Chiapas, believed that burning copal was akin to grinding corn and as the mass of corn becomes food so did the smoke become spirit-sustaining tortillas to the deities. However, the very idea of a tortilla was a rather late arrival to the Maya who for centuries used tamales (of maize and copal) as their sacrificial offering of choice until switching to tortilla under the increased influence of Aztec culture prior to colonisation. While the practice of copal tortillas still exists in the Lacandón belief system today most people do not believe that they are literally feeding their deities. Instead, they see it as a metaphor.

Copal also had another strong symbolic parallel in the minds of ancient Mesoamericans, that of blood. While everyone likes to focus on the dramatic scenes of hearts extracted atop pyramids, the concept of blood sacrifice was more complicated. Much like copal and maize, blood was a precious resource and seen as a needed sacrifice to literally make the cosmos keep going. Within the confines of their worldview, the people felt they owed a blood-debt to their deities that had to be paid. While human sacrifice did happen, there was also animal sacrifice and smaller less heart-ripped-out-ya-chest types of human blood sacrifice. People pricked themselves with ceremonial cactus spines to draw blood to include in their divine pleas for intercession. That blood was often sprinkled on the censers burning copal at the temple, mixing blood and copal. Just as the faithful pierced their skin and bled for the gods so too were the trees pierced and bled to extract their precious sap to feed the gods. The blood of the people and the blood of the trees mixed and sent to heaven.

The connection between blood, maize, and copal is not all ancient history either. The Mam Maya of Guatemala continue to perform a planting ritual called pomixi or the copaling of the maize, part of the ceremony involves participants dripping sacrificial blood from pricked fingers over copal then burning it in censers with its aromatic smoke wafting over the corn seeds waiting to be planted. While I don’t personally think that blood rites helped much, fumigating grains with copal has been shown to increase seed yields by inhibiting bacterial growth that could lead to seed rot, so there was indeed a reason this tradition lasted as long as they did.

Unseen Worlds

Olfaction in Mesoamerican cosmology had an ephemeral nature to it that transcended planes of existence and becomes a way to interact with and perhaps influence the spiritual word. This type of magic of olfaction was also used by the Sierra Popoluca people of Tehuantepec. The jawbone of a deer killed in a hunt was turned into a ritual object by smoking it with Copal. The transubstantial and transcendental qualities of the scent of copal were thought to tether the animal’s spirit to its remains thus allowing the community’s shaman to recall the deer-spirit back from the spectral world to its bones and by doing so harness that energy to bless the community’s hunters with a successful mission.

The great power of aromatic substances as ritual tools is that odour is both earthly and otherworldly. It affects us emotionally and links us to our cultural and familial pasts. Copal is a tangible material, yet it creates a time and space separate from the day-to-day bustle of life. It represents the unseen world. It is there, you can smell it, but you can’t see or touch it, just as you can’t see your departed loved ones, but your love for them is still part of this world. So what better way to commune with spirits then through olfaction.

Copal & the Day of the Dead

Ok, Nuri can we now talk about the Day of the Dead? Yes, gentle reader let’s do this!

We’ve established copal is the aromatic heart of the Americas. In Mexico, it has an ancient tradition as an intermediary substance with the divine. It was also a material associated strongly with the land and the indigenous people. Copal, along with many aspects of indigenous religions were suppressed under Spanish colonial rule. Before colonisation, the yearly celebrations to Mictēcacihuātl took up most of August for the Aztecs. However, under Spanish control, Mictēcacihuātl was declared a demon by the Catholic Church and ceremonially exorcised from the land. The Christian festival of All Saints was promoted as an alternative.

Enormous effort was made to crush the indigenous religion. It wasn’t only a matter of Christian missionary zeal but also a means of disrupting the centres of power in the society to make it easier to control. Despite a concerted effort to constrain the expressions of loss and memorial, the Spanish could never completely eliminate the collective need for catharsis around death and a connection to one’s ancestors. As Mictēcacihuātl worship went underground All Saints/ Day of the Innocents and All Souls Day, not surprisingly, became increasingly important and filled the memorial space that the Mictēcacihuātl ceremonies once held. So while the observance of All Saints became sacred, it didn’t remain wholly European and instead also adapted. In time, what developed was a unique practice in the Day of the Dead that reflected the ancient Mesoamerican past, colonial scars, and a synchronised future.

Copal burning would be forbidden at Church services in Mexico and Guatemala from the 16th century until the 1890s; around the same time that the Virgin of Guadalupe was coronated by the Church and ideas about La raza cósmica were shaping Mexican identity. The Church footed the bill for the import of frankincense and myrrh for centuries instead of using a substance too closely associated with paganism.

While the Church was iffy about using copal, the people never were, and whether it was indigenous shamans still engaged in spiritual pursuits or middle-class devout Catholic housewives burning it before an altar to the Virgin, copal was, and is still, used as part of folk and domestic religious expression in Mexico and Guatemala.

What does Día de Muertos smell like? The spiciness of the cempazúchitl (Aztec marigold) and copal. Copal takes a place of importance on the Day of the Dead both graveside and at familial memorial altars as an essential component of the ofrenda. The ofrenda or offerings left in memory of the dead are symbolic of the hospitality due to a traveller. Salt, water, and bread are essential. Toys for children and the deads’ favourites be they foods, drinks, or cigarettes reinforce the personalities of the departed. These celebrations aren’t for abstract ancestors but for those that one knew and lost.

In the course of writing this post, I informally surveyed 19 people, mostly friends and friends of friends, about why they burn copal with their ofrendas. Their responses were in line with much of the research on the modern day practice of Día de Muertos. Some said it wards off evil or that it purified the altar or grave. Others said that it represented the element of air or fire as earth, air, fire, and water should be presented. One young woman from Mexico City felt that copal served as a reminder of the transient nature of life. When I asked who taught them to set up their ofrenda and the preparation of incense the answer was overwhelming “my mom” or “my grandmother” which reflex that this is still very much a living tradition, taught in families and like many folk practices comes to embody multiple parallel meanings.

Despite this diversity what I found interesting was the prominence of three responses. The first was that incense elevated one’s prayers to God or that it was the bond that unites heaven and earth. This sentiment is not unlike those of their pre-Colombian ancestors. The fragrance served as a transcendental expression of one’s prayers being carried to the divine, just now it’s a god with a capital G. The second was that copal helped lead the dead home, either to their graves or their family’s house so that they could be with their family to celebrate. This concept of scent as a trail or a bridge to the afterlife harkens back to the use of the deer’s jawbone by the Sierra Popoluca. Finally the third was that the strong aroma of the marigolds and copal were part of the spiritual essence the dead would consume along with the spiritual essence of the food. Which again ties copal as a maize substitute in ritual consumption.

I asked one middle-aged woman who was exceedingly patient with me over email, “Why copal now, you could use anything you’d like why not say frankincense, or patchouli, or myrrh or perfume or anything else you might like to smell?” Her response again knit the people, the land, and scent back together:

“Because they’re not Mexican and this [Día de Muertos] is quintessentially Mexican, it has to smell Mexican. My family is buried in this soil, with these trees and plants and rain. I want to connect to them and they are part of this place, so it has to smell like this place. It has to smell like home.“

At the end that is what it is all about, the memory of those we love and the smell of home.

Want to Know More?

Copal Fragrances

Copal isn’t a traditional raw material in perfumery, but interest has been growing in the Indie fragrance market. These are some of my favourite copal drenched scents.

Become the Shaman by DSH Perfumes

Antimony by House of Matriarch

Grey’s Cabin by Solstice Scents

Likewise by Strange Invisible Perfumes

Want to Burn Copal?

Copal is a beautiful resin to burn directly. As with any resin or wood incense, I strongly urge you to use a mica plate between the heat source and the material to appreciate the full aroma of the product without singeing. I only use Shoyeido plates. I also suggest if possible to buy copal in Mexico from local producers but barring that, I’ve listed two online sources I like below

UK: Tredwell’s Copal Incense Resin by Tredwell

US: Copal Incense by Bouncing Bear Botanicals

Want to Read More?

Here are some resources from this article you might find interesting for taking a deeper dive into the subject

- Ecology of Plant-Derived Smoke: Its Use in Seed Germination By Lara Jefferson

- Crossing Boundaries: Mayan Censers from the Guatemalan Highlands by Sarah Kurnick

- The Maize Tamale in Classic Maya Diet, Epigraphy, and Art by Karl A Taube

- Objects made of copal resin: a radiological analysis by Naoli Victoria Lona

Footnote

*The same can’t be said for the Indian Copal Tree (Vateria indica) while not related produces a similar resin and is critically endangered as well as some sub-species of American Copal, like the Panamanian Copal tree, which is near threatened. So it is vital that each and every one of us are good stewards of our perfumed world so that our kids will be able to enjoy these pleasures as well.

One Comment

Comments are closed.