If you are a fan of fragrance history, you may be familiar with the Egyptian god Nefertem. He is the personification of the Cosmic Lotus in the Egyptian creation myth. Nefertem is the protector of dawn and patron of Egypt’s beloved blue lotuses. Nefertem rises from the river at daybreak each morning with his flowers and fills Raas nostrils with cosmic perfume. Nefertem’s beauty gives the weary old sun god the strength to shine one more day.

So it is no surprise that most people today think of Nefertem as the major deity associated with ancient Egyptian perfumery. Indeed, in antiquity, he was a beloved deity of pleasant aromas (both natural and human-made), but there was another god.

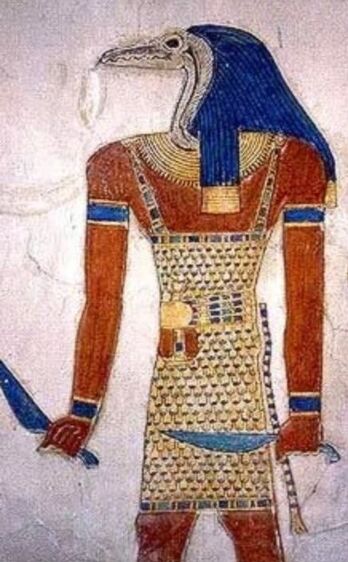

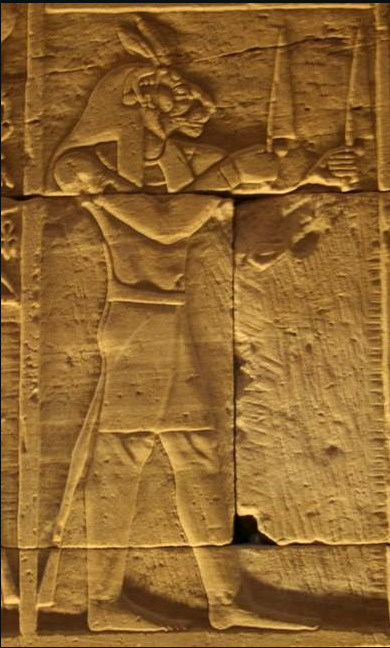

A god whose name was written on the oil presses and whose terrifying visage was carved into the walls of perfume storehouses. This deity was loved by the perfumers of Fayoum, but it was not our dear sweet Nefertem. It was Shezmu-the lion-headed, knife-wielding executioner of the Underworld. He had many epitaphs, some of which would make excellent death metal albums: Lord of Blood, Slaughter of Souls, Butcher of the Gods, He Who Dismembers. Yet, Shezmu had a softer side, as some of his other epitaphs reveal: Maker of Precious Oils, Lord of Perfume, Great Maker of Ra’s Oils, Lord of Unguent.

Was he a demon or a god? Kind of both, they called him both in antiquity, but they didn’t mean devil like we do today. I like to think of Shezmu as an immortal with…diverse interests. If you are unfamiliar, allow me the pleasure of introducing you.

Demon of the Wine Press

Shezmu was a complicated character from his earliest iteration. The hieroglyphic letters of his name also spell the word for press (for wine or oil), and sometimes he is represented with just the hieroglyph of a press  . So we know from the beginning of his worship, Shezmu was associated with wine and oil manufacturing, two essential crafts in ancient Egypt. We also know his worship goes back to the Old Kingdom and continued through the Ptolemaic period. Vessels found near the Pyramid of Djoser indicate Shezmu already had a priesthood before 2,670 BCE.

. So we know from the beginning of his worship, Shezmu was associated with wine and oil manufacturing, two essential crafts in ancient Egypt. We also know his worship goes back to the Old Kingdom and continued through the Ptolemaic period. Vessels found near the Pyramid of Djoser indicate Shezmu already had a priesthood before 2,670 BCE.

The type of rudimentary press he was associated with consisted of twisting a product in a cloth over a vessel, sometimes using a wench for torque. This type of work also included actions like grinding materials, chopping wood, stoking cooking fires and moving large cauldrons. Working a press in ancient Egypt required an enormous amount of physical strength.

So it isn’t surprising that the God of the Press is depicted as a big burly beefcake. However, Shezmu is also associated with horrific violence. Many of his icons feature him carrying duelling butcher knives, which he would use to dismember the bodies of wrongdoers and gods alike. The Coffin Texts depict Shezmu as the demonic headman of Osiris. He would rip the heads of the unworthy off with his bare hands and put them in his press to squeeze out their blood like juice from his grapes. This violence, while almost comically gory, was also deeply symbolic.

The connection between blood and alcoholic beverages like wine and beer was a potent metaphor in the Egyptian mythos. Blood was the life force of people, giving humanity animus and power. The juice of the grape was also its life force, and the creation of alcohol was a capturing of that spirit. The fact that Egyptian wine was red and its beer was often tinted drove home this blood analogy. We see that play out in the myth of Sekhmet. When the lion-headed goddess is sent to punish humanity, she grows drunk on the power of slaughter. The day is saved when she is tricked into drinking alcohol in lieu of blood. She becomes intoxicated and decides she’d rather not murder the whole world. So to the Egyptian mindset, it made sense that Shezmu was associated with both wine and blood. He was the extractor of life force.

This is clear in the Pyramid Text of the 5th dynasty pharaoh, Unas. In Utterances 273 and 274, Shezmu is presented as hunting and slaughtering the gods so Unas could consume their power and become a god himself. This text, referred to as the Cannibal Hymn, is actually preserving a pre-dynastic power-consuming ritual. In this ritual, the king would slaughter and eat parts of several sacrificial bulls representing various gods. The king did this in the hopes that he wouldn’t just live again in Duat (Egyptian afterlife) but transform into a celestial ruler on the same footing as the gods. Shezmu was critical in that power extraction and used the tools of his trade.

Behold, Shezmu has cut them up for Unas, he has boiled pieces of them in his blazing cauldrons. Unas has eaten their words of power, he has eaten their spirits. -The Cannibal Hymn

Lion-headed Gods are Complicated

Another hint to Shezmu’s dualism is that he is often depicted as a lion-headed man. Lion-headed gods tended to represent contradictory but interconnected states in Egyptian mythology. Sekhmet is the goddess of plagues and warfare but also healing. The Nubian god Apedemak was the god of war and peace. Maahes was the Lord of Massacres and protector of women and children in warfare.

Shezmu, as a wine god, was a god of industry and carnage but also a deity of joy and celebration. Wine encompassed all three: hard work to make, bloody drunken fights, and celebrating happy times. Shezmu was a frequent companion of Ma’at (goddess of truth and personification of cosmic order) in literature and art. Yet, he was also associated with Apep, the chaos serpent and personification of Isfet (disorder, misrule, chaos).

The philosophical concepts of Ma’at and Isfet represent a complementary but paradoxical dualism that was at the core of Egyptian thought. Both states of being needed the other. Human reality rested somewhere between the endless boring perfection of Ma’at and the absolute mess of Isfet. Interestingly, the concept of Isfet doesn’t come out of an idea of original evil; instead, it is born from humanity’s free will. Egyptians saw society as a constant act of creation, striving for Ma’at and resisting our baser desires that would lead to chaos. Because we can choose our fates, anything is possible, including extraordinary evil.

Shezmu, as a deity, personifies this dualism. If humanity uses its skills for good, we can make wonderful and beautiful things that enrich our lives. If we use those same skills for evil, we create chaos. The version of Shezmu you meet in Duat, the boozy perfumer or the butcher, is created by your actions in life. As it says later in the Cannibal Hymn, ‘…He casts wickedness on him that is wicked and truth upon he who follows truth.’ We get the Shezmu we deserve.

God of Perfume: Extractor of Life-But Less Gruesome

Shezmu’s worship lasted nearly 3,000 years. While he never completely lost his tough-guy persona, the gentler Ma’at side of Shezmu was preferred by the New Kingdom. Not only was Shezmu a god of wine, but he was also a god of perfume and unguent.

Egyptian perfumery was oil-based. Moringa, olive, sesame, almond, caster, and pine nuts were popular suspension oils into which resins and plant materials would be infused. Shezmu’s oil press was essential for creating base oils and the perfume-making process. The majority of ancient Egyptian perfumery techniques revolved around steeping or heating aromatics in oil, pressing and filtering those materials to extract every last scent molecule, and then repeating the process.

Fragrance creation still fits into Shezmu’s basic portfolio as an extractor of life essence. However, now it was the souls of flowers he was stealing. Aromatics, in themselves, were seen as spiritually powerful and connected to the divine. This is less of a segue and more of a refinement of Shezmu’s nature into its highest art form.

Fragrance played multiple roles in Egyptian society. Simple oils were a necessity to protect the skin from the harsh climate. Opulent perfumed oils were a luxury and a cosmetic. These products served as medicine and ritual tools for divine communication. They were also vital to the embalming process, and Shezmu is essential to Egyptian mortuary cults because of this connection.

Our ancestors were not terribly burdened by putting these things into separate categories. The line between practical and magical was thin and negotiable. Perfume-making was a high culture activity that embodied Ma’at principles. From the cacophony of odours found in nature, humans could extract a few magical essences and create something of rare beauty. Unlike wine, which has its apparent downfalls, perfume was a form of creation with little risk of bringing more Isfet into the world.

Protector of Sacred Perfume

By the Greco-Roman period, Shezmu is fully embraced as the patron of perfume-making. This was also the period which saw Egyptian perfumes coveted worldwide for their superior quality and medical/magical attributes. The perfumers of late antiquity Egypt were sophisticated professionals running international supply chains and making globally desired products. In many ways, their work would seem familiar to perfumers today, right down to dealing with taxes and arguing with regulatory bodies. However, nothing in contemporary perfume equates to producing sacred oils for cult purposes by priest-perfumers.

There is no doubt that Nefertem was important to ancient Egyptian perfumers. Nefertem was the keeper of all pleasant aromas and was the one that allowed them to ascend to the gods. However, Nefertem didn’t have a priesthood, and he didn’t have his own cult centre. There was a chapel dedicated to Sokar and Nefertem in Seti I’s funerary temple in Abydos, but it wasn’t a significant worship centre. More substantially, Nefertem was part of the Memphis Triad, a holy family of deities with his father, Ptah and mother, Sekhmet. The Memphis Triad was influential in the Old Kingdom, but eventually, Nefertem would be replaced by Imhotep and sometimes Maahes.

Shezmu, on the other hand, had a priesthood going back to the Old Kingdom. Fayoum was his major cult centre, but he also had temples and active cults in Edfu and Dendera. His cult centres made wine and perfume on site. Both categories would have profane and sacred uses. Ritually prepared oils and unguent would be applied to cult statues and ritual tools to consecrate them. As a deity of perfume-making, Shezmu was a protector of sacred perfumes. They would be used in the ritual preparation of the dead, more so for magical purposes than for practical preservation. It is reasonable to assume in his role as patron of perfume-making, with a priesthood of perfumers, that those in the perfume trade actively worshipped Shezmu.

Nefertem & Shezmu: Unlikely Pals

The wonderful thing about ancient Egyptian religion is the focus on the push and pull of dynamic and contradictory forces. Nefertem and Shezmu are not enemies but two sides of the same coin. Sometimes they are even presented as brothers, with Nefertem wearing the lion’s head and Shezmu as the beautiful youth. The god Maahes seems to be a synchronisation of both of them.

Both Nefertem and Shezmu play a part in the sun god’s daily procession, which I think is quite profound. Nefertem greets Ra in the morning with all the beautiful smells of the natural world and gives the god courage. He accompanies Ra throughout the day until it is time for his flowers to retire for the evening. You know Shezmu has boarded the celestial boat in Nefertem’s place when the twilight sky turns blood red. There he comforts Ra with all his lovely perfumes to tempt, soothe, and delight. Shezmu also gets to unleash his murderous blood lust on the chaos monsters that attack Ra’s ship each night. He is always successful because the concept of Ma’at remains come daybreak, and the cycle starts all over again.

Death & Perfume In Ancient Egypt

This post is part of D/S’s series on the aromatic death rituals of ancient Egypt. Check out more in the series below

You must be logged in to post a comment.